Go’s html template package has some really powerful safety features but is unfortunately not designed to be as simple as some of the other template packages I’ve used in the past.

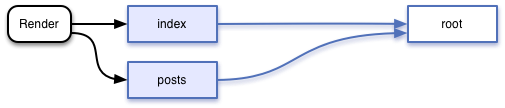

In most templating packages I’ve seen, inheritance is expressed inside of the

template itself. So if you have two pages index and post which inherit

from a common root, the inheritence is expressed inside of the templates

themselves. It’s sufficient to parse index and post in code, and let the

templating engine handle the lookup of root on its own:

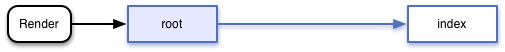

Go’s templates don’t allow a template to specify which template(s) it inherits from, only ones which the root template calls. Therefore the association points downstream, which means that you call render on the parent.

Therefore inheritance needs to be managed in code. Luckily, a template exposes

a Clone method which allows you to copy a parsed template and then populate

any empty sections on a per-clone basis.

It’s easy enough to define a simple class which allows you to parse a set of

files as a root template and then split that into new templates as needed.

Following is a rough example. Instantiate it by calling

NewTemplatesFromGlob, specifying a glob pattern which defines the entire set

of base templates:

type Templates struct {

tmpl map[string]*template.Template

}

func NewTemplatesFromGlob(glob string) (t *Templates, err error) {

var (

root *template.Template

)

if root, err = template.New("root").ParseGlob(glob); err != nil {

return

}

t = &Templates{

tmpl: map[string]*template.Template{

"root": root,

},

}

return

}

func (t *Templates) Split(from string, to string) (err error) {

var (

tmpl *template.Template

)

if tmpl, err = t.tmpl[from].Clone(); err != nil {

return

}

t.tmpl[to] = tmpl

return

}

func (t *Templates) Get(key string) (tmpl *template.Template) {

return t.tmpl[key]

}

For a concrete example, assume you have the following template structure:

templates/root/base.html

This is the base all clones will inherit from. Note that the root template

is explicitly defined, as ParseFiles seems to break if it isn’t (even though

you should be able to have a single unwrapped template - this may be a bug with

Go’s library).

Note the empty head and body templates. Because they’re empty, they’ll be

overrideable in clones. Trying to override a populated template will

unfortunately cause an error.

{{define "root"}}<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

{{template "head" .}}

</head>

<body>

{{template "body" .}}

</body>

</html>

{{end}}

{{define "head"}}{{end}}

{{define "body"}}{{end}}

templates/root/post.html

For the sake of the example, there’s another template included in the base

called post. This can be called from any cloned template, so it shows how

you can make a set of common templates which may be called by individual

overrides.

{{define "post"}}

<div class="post">

<h2>{{.Title}}</h2>

{{.Body}}

</div>

{{end}}

templates/index.html The index page just defines a simple body.

{{define "body"}}

<h1>Index</h1>

<p>Hi! Check out the <a href="/posts">posts</a></p>

{{end}}

templates/posts.html

The posts page iterates over the data and calls the post base template.

{{define "body"}}

<h1>Here are posts</h1>

<div class="posts">

{{range .Posts}}

{{template "post" .}}

{{end}}

</div>

{{end}}

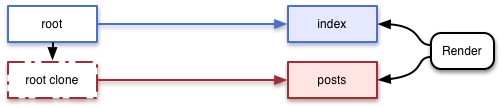

Building the templates in code requires parsing the files in templates/root

and then splitting that into individual posts and index clones, then

calling ParseFiles to override the empty body template in root.

The beauty of Go is that this is probably clearer when expressed in code:

var (

err error

templates *Templates

)

if templates, err = NewTemplatesFromGlob("templates/root/*.html"); err != nil {

// Handle error

}

if err = templates.Split("root", "posts"); err != nil {

// Handle error

}

if _, err = templates.Get("posts").ParseFiles("templates/posts.html"); err != nil {

// Handle error

}

if err = templates.Split("root", "index"); err != nil {

// Handle error

}

if _, err = templates.Get("index").ParseFiles("templates/index.html"); err != nil {

// Handle error

}

Rendering is very straightforward and relies on the built in Execute method.

Just Get the template you want to render and call the built-in package as you

would normally:

var (

out string

writer *bytes.Buffer

data = map[string]interface{}{

"Posts": []map[string]interface{}{

map[string]interface{}{

"Title": "Foo",

"Body": "Bar",

},

},

}

)

writer = bytes.NewBufferString("")

if err = templates.Get("index").Execute(writer, data); err != nil {

// Handle error

}

out = writer.String()

fmt.Printf("INDEX:\n%v\n", out)

writer = bytes.NewBufferString("")

if err = templates.Get("posts").Execute(writer, data); err != nil {

// Handle error

}

out = writer.String()

fmt.Printf("POSTS:\n%v\n", out)

This produces the following output:

INDEX:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Index</h1>

<p>Hi! Check out the <a href="/posts">posts</a></p>

</body>

</html>

POSTS:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Here are posts</h1>

<div class="posts">

<div class="post">

<h2>Foo</h2>

Bar

</div>

</div>

</body>

</html>

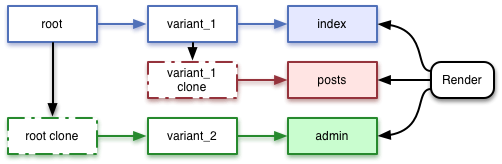

You can build more complicated template hierarchies by adding wrapper templates. In the following diagram, I’ve called them variants:

Imagine you have a set of pages which depend on an administrator menu which you

wish to insert above or wrapping the body content. The most direct approach

I’ve discovered involves creating another layer of template and then creating

both regular and admin variants.

templates/regular.html

{{define "body_content"}}{{end}}

{{define "body"}}

{{template "body_content" .}}

{{end}}

templates/admin.html

{{define "body_content"}}{{end}}

{{define "body"}}

<div class="admin_menu">

Admin menu

</div>

{{template "body_content" .}}

{{end}}

Then every page living in the third tier of templates must implement

body_content instead of body. Because body_content is used consistently,

you could theoretically make any page an admin page just by changing its

variant and reparsing.

It’s honestly not the most intuitive system. I’m not really sold on the utility of managing template inheritance through code. I do believe that it should be possible to extend the rudimentary template management framework I’ve included here into a real library which would be able to infer inheritance through some sort of template file metadata. For example, imagine a directory structure like the following:

templates/

+- base.html

+- post.html

+- admin/

| \- admin.html

\- regular/

+- index.html

\- posts.html

All of the inhertance could be inferred by the directory path, which would keep template logic contained to the template files and organization themselves.

Eventually someone may port a more sophisticated system to Go, but it would

lose a lot of the attractive security features already implemented in

html/template. Learning to juggle clones may be the best way to present

untrusted data in HTML format to your website’s users.

Comments? If you have feedback, please share it with me on Twitter!